Flight deck

FLIGHT DECK EVOLUTION

Building an aircraft is very much a chicken and egg problem; everything is intrinsically linked and changing one thing will have a knock-on effect to potentially many other aspects of the airframe. This means aircraft design and development is a very fluid process, with surprisingly large changes occurring late into the programme – sometimes even after first flight has taken place. With that said, the more you can get right on the first go, the better.

Thankfully, a huge amount of theoretical work can be undertaken before committing even a gram of aluminum to the press. Utilising a knowledge of material science, wind tunnel testing, and generally understood best practices from prior developments, an experienced aircraft manufacturer can get something from the drawing board to the air without noticeable design change.

There are, however, some aspects that cannot be so easily calculated or planned for: the flight deck. Beyond the ever-changing technology that, especially in the 80s and 90s, was drastically changing cockpit panels from clock-shops to television screens, the flight deck is primarily to be an interface between the human pilot, and the machine aircraft. Humans are annoyingly hard to predict, simulate, or generally understand. They also complain a lot – especially if there’s a pilots’ union to uphold. Perhaps a sore neck from twisting to see a gauge, a lever that is accidentally bumped with the knees when getting up, or an instrument that is obscured by something else from the normal flying position.

For this reason, a flightdeck will usually go through many iterations, from initial drawings and physical mock-ups to test airframes and final production. Then finally tweaks and changes over the lifetime of the aircraft as both technology changes or improves, and operators learn more about what they need from the aircraft.

The ATP went through this process in quite an interesting fashion – being a successor to the HS748, many design aspects were initially carried over but only some stayed into production. It was also the time of the ‘electronic revolution’ in commercial aviation, when manufacturers were ditching the tried-and-true dials, contactors, and relay-based systems in favour of cutting-edge first-generation digital technology.

FIRST LOOK

In the Spring of 1984, British Aerospace began publishing marketing material featuring the up-coming ATP, however even the wooden fuselage mock-up hadn’t been completed by this point so the sales literature exclusively featured artist impressions and drawings. Starting with a marketing photograph of the ‘Super 748’ mock-up flight deck, an aircraft that never went into production, BAE painted over the panels and added several details. No doubt these were guided by the design department, so it gives us our first look at what they had in mind for the time.

Right away, it is clearly an ATP cockpit – but as we look closer, the less we recognize. The screen hardware resembles that of the Honeywell ED-800 EFIS, later seen in the J41; given the wooden mock-up hadn’t even been completed yet, it’s entirely possible they had yet to discover that off-the-shelf EFIS/CRT display systems wouldn’t fit in the small gap between the main panel and the narrowing fuselage around the nose, and be forced to have Smiths build a bespoke ‘short’ CRT EFIS screen at great expense.

There are a surprising number of design points cemented already: the Audio Control Panel from the BAe parts bin, the Center Warning Panel location, the weather radar with what appears to be an electronic checklist already displayed on it. Even the novel flap lever mechanism, requiring pilots to move it alternatingly left and right to extend or retract each flap position. This is no doubt a response to high profile accidents at the time involving flaps being unintentionally fully retracted during missed approaches, causing aircraft to stall and crash.

The decision had also been made not to extend the EFIS to include the engine instrumentation, instead opting for classic analogue dials built by Thomson-CSF. The idea of full ‘glass cockpits’ was in it’s infancy at the time, with the first airliner featuring digital engine displays, the Boeing 757, flying just 2 years prior to this illustration.

Beyond this, the main panel feels bare – missing many buttons, knobs, and instruments. The EFIS and autopilot control panels seem to be ‘stuck on’ wherever they’d fit. Certainly, all is pointing towards a very early concept. Several aspects are carried over from the HS748: the rotund control column, rudder pedal assembly licensed from Heath Robinson, control lock and trim wheel are the stand-outs.

This illustration was proudly displayed on the fuselage mock-up.

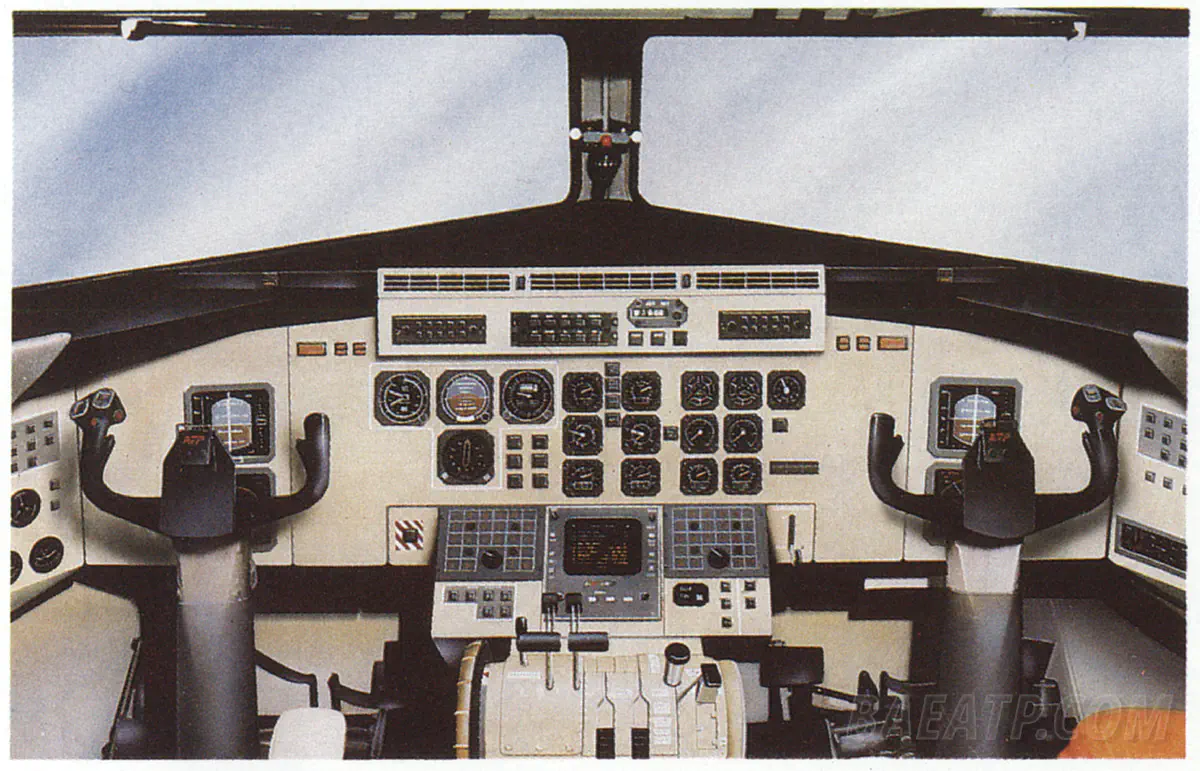

CONCEPT REALISED

It was at the Farnborough Airshow in September 1984 that the first physical ATP cockpit section appeared.

Still a concept, but now matured with real panels, instruments, levers, and switches, all in close to their final production layout. Notably missing are the circuit breaker panels, side panels, and cockpit window surrounds. The control column is now inexplicably wrapped in leather, and the gear lever assembly looks as though it has been cut from a baked bean tin. There are some other human-interface discrepancies to the production model here, namely the control stand: roll-over levers are uncomfortably far away, no doubt making taxiing a challenge at best, and the fuel levers are squared off rather than the eventual rounded profile with teacup handle.

The area navigation system is however almost identical to production aircraft, featuring the King 660